An audience gathered in the late afternoon of July 5. The cadence builds in every lilt of the professor’s powerful words. Yes, poetry is of the past, but it can also be tapped as a resource to think about language and identity, particularly of Ilokanos.

A late afternoon with Dr. Aurelio Agcaoili is a return to Ilokano poetry, now seemingly cast into oblivion because of the pressures of everyday living. Held in the historic Café Leona, the house of first world-renowned poetess, Leona Florentino, “Ti Biag Ket Maysa Daniw / Life is a Poem” is a heartfelt celebration of the spoken word—not only for nostalgic feelings but also for the power of the pen to engage with the political.

Agcaoili is a professor of Ilokano, pioneer of Ilokano and Amianan Studies, and incoming chair of the Department of Indo-Pacific Languages and Literatures, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. He is also the founder of NAKEM, an organization of scholars and cultural workers for linguistic diversity and emancipatory education.

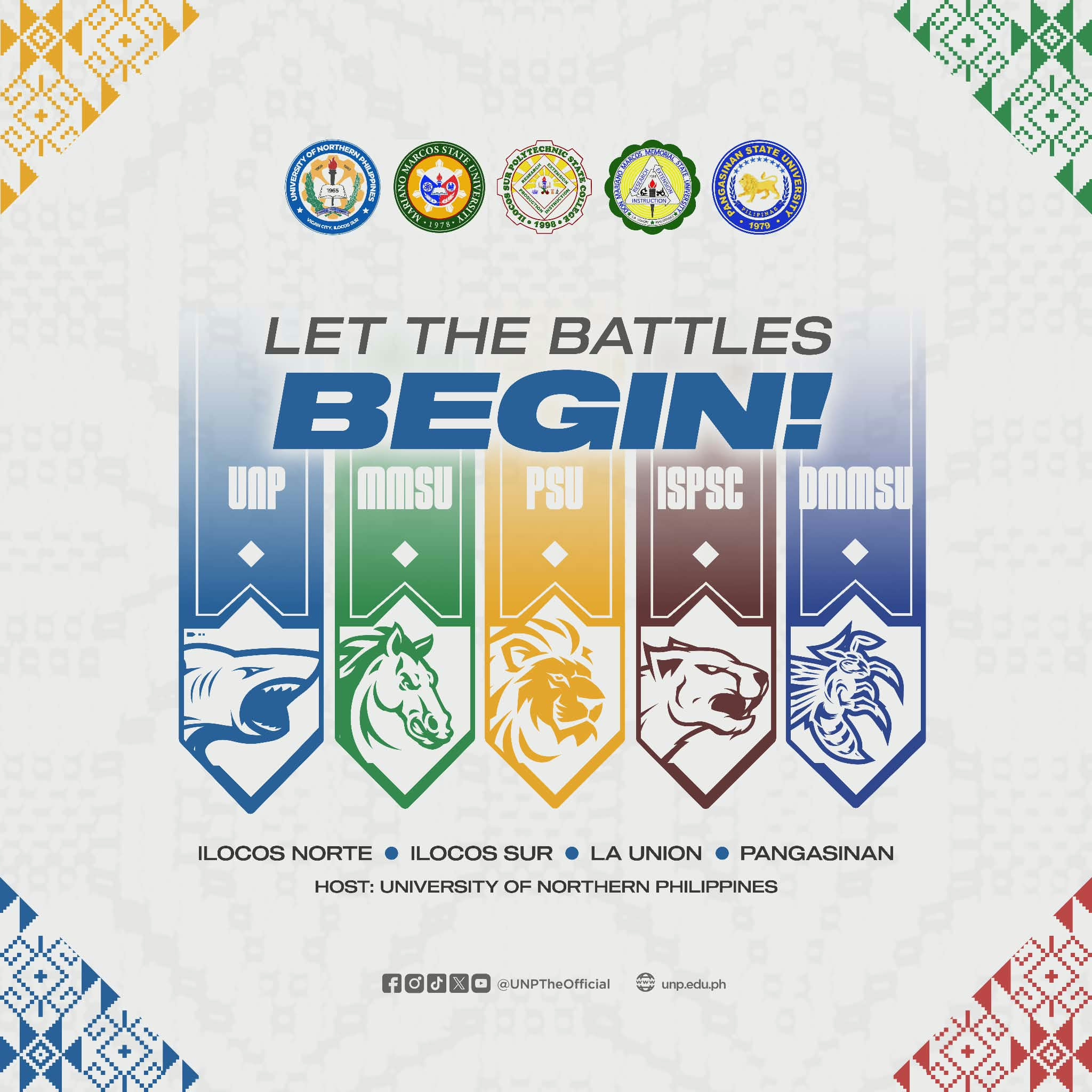

The event is a celebration of the renewal of the pact between the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and the University of Northern Philippines. As such, UNP is resolute in widening its circles in the international community through academic and cultural programs.

The poems Dr. Agcaoili read in the event amplify Ilokano voices in the diaspora, critique Filipinos’ positionality as “remaindered life” (in Neferti Tadiar’s words) in the current global order, and textualize experiences of homelessness and homing of those who left home and are looking for happiness and hope, elusive they may be.

According to him, his poetics—like many others in the diaspora and as he articulated in his oeuvre of poetry, fiction, and scholarship—is that of homelessness and homing in faraway lands. This is borne out of the many years of Ilokanos’ diasporic experience.

For instance, “Agbirbirok ni Ilokano iti Ilina” (in a move reminiscent of the modernist theatrical piece “Six Characters in Search of an Author” by Luigi Pirandello), once performed by his students into a choral performance, articulates the angst of having been removed from the homeland of one’s ancestors. Their tenuous relationship with the Motherland, nevertheless, is pursued such as in their attempt to speak Ilokano. The translingual practice in the poem—of both Ilokano and English—is emblematic of the meshing of diasporic Ilokanos’ cultures and identities in the hostland.

Another poem is about overseas contract workers, a common experience among Filipinos. The poem textualizes lives of the deracinated in the global order characterized by “remaindered lives,” of capitalist accumulation which “depends on producing life-times of disposability” and “practices of living that exceed the distinction between life worth living and life worth expending,” as scholar Neferti Tadiar notes.

Agcaoili’s poems reveal, on the one hand, that poetry is one manifestation of the Ilokano voice. He pointed out that long ago, even ordinary Ilokanos, after a day in the ricefields, recited poetic lines at the accompaniment of the guitar or banduria and basi. On the other hand, the poetic voice in his poems engages with the political—as is often the case in the Philippine literary tradition.

A bard of our times, even if he is far away from the Ilokandia home, Agcaoili’s poetic voice is a singular and sonorous one in times of distress and relief, of tempest and solace.